In February 2017, Ashton Kutcher and his tech company Thorn went viral. Thorn: Digital Defenders of Children is an anti-trafficking organisation that focuses primarily on the use of the internet in facilitating the sexual trafficking of children. Kutcher addressed the United States Senate Foreign Relations Committee to speak about ending modern day slavery, recounting the work that Thorn has done in co-operation with larger tech companies and law enforcement. The Global Slavery Index estimates that there are 45.8 million people living in slavery and a large percentage of victims are being sexually exploited. Thorn and other organisations are recognising the role that the internet plays in human trafficking and are working to fight it.

As commerce moves online so does the seedy underbelly; the so called ‘dark web’ is used to sell everything from drugs to human beings. Research undertaken by Thorn revealed that 63% of underage sex trafficking victims had been advertised or sold online. Kutcher spoke of Spotlight, the online software created by Thorn that turns data on sex traffickers and victims into an asset for US law enforcement to use. As more people use Spotlight, it becomes more efficient and saves unnecessary workload for those working on trafficking cases. The details of how Spotlight works are not available online so that it is more difficult for traffickers to try and work around the software. Statistics from Thorn state that in the past year over 6,000 victims have been identified using Spotlight, making clear the role that online advertising sites play in trafficking.

Senator McCaskill addressing backpage.com for their involvement in online trafficking

Online exploitation means that victims are abused from perpetrators both in person and through the internet. The dark web is not a secret, and it is easily accessible by anyone. This means that people across the world and from all different backgrounds have access to a huge catalogue of sexual trafficking victims. One of the easiest way for traffickers to advertise underage victims is on sites such as backpage.com, sites which functions like Craigslist or Gumtree, offering goods and services. A huge amount of revenue was generated from their ‘adult’ advertising section, but in January 2017 this section was taken down. Despite evidence suggesting that they edited adverts which contained words alluding to underage victims, backpage.com has repeatedly denied that their website facilitates the sex trafficking of underage victims. Instead they have framed the accusations as an attack on free speech, claiming that the only way to stop the harassment from the government was to shut down the adult section. The investigation into backpage.com was not one of government censorship, instead it was an attempt to quell the growing number of children being advertised online for sexual exploitation.

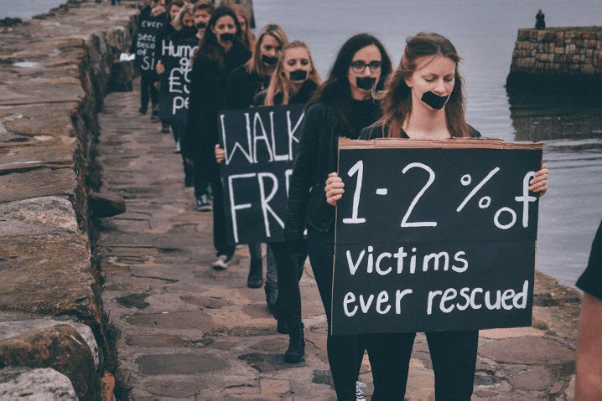

Whilst Thorn and other organisations are making huge progress in identifying traffickers and victims, the journey does not stop there. There are many organisations, charities and individuals who are dedicating time and resources to the rehabilitation and recovery process of trafficking victims. Some of the largest and most well-known organisations fighting human trafficking include International Justice Mission (IJM), Stop the Traffik, and A21. All of these organisations have utilised the internet and more specifically social media to raise awareness and support for their missions. On February 23rd, social media was overrun with the hashtag #enditmovement accompanied by photos of red crosses. This was to raise awareness for the ‘Shine a light on slavery’ campaign run by the END IT Movement, a coalition of international anti-trafficking organisations. The 2016 campaign made more than 144 social media impressions, reaching an immeasurable amount of people worldwide. Events such as the Walk For Freedom which was organised by A21 happened in many cities across the world, and even here in St Andrews. High profile celebrity supporters help raise awareness for these organisations indeed during his address Kutcher was wearing the red cross of the END IT Movement.

A21 Walk for Freedom held in St Andrews, photo by Alex Shaw

Alongside the important work done by anti-trafficking organisations, there has been a conscious effort by governments worldwide to tackle the issue of modern day slavery. The hearing that Kutcher spoke at was held in relation to the Shine a Light on Slavery Day with the aim to assess US efforts to end modern slavery and human trafficking worldwide. In October 2016, the International Sex Trafficking Summit was held in Waikiki, Hawaii. Representatives from countries including the US, the Philippines and Thailand attended with the intention to discuss strategies and create working relationships based on the common goal of prosecuting sex traffickers. As made evident by the work of Thorn, online traffickers are difficult to pinpoint and even harder to prosecute. UK Home Secretary, Amber Rudd, has recently announced that £40 million will be given to government agencies and organisations that deal with the sexual abuse and exploitation of children. The National Crime Agency will receive £20 million to ‘tackle online child sexual exploitation’. It is evident that across the world governments and those with power are recognising the dangerous role that the internet plays in the exploitation of children, and they are working together to address this.

Collaboration between authorities and charities has started the difficult process of working to eradicate sexual slavery and exploitation. Kutcher closed his emotional address with the profound statement, “technology can be used to enable slavery but it can also be used to disable slavery, and that’s what we’re doing”. The impact of smart technologies will undoubtedly allow progress to happen more quickly and efficiently across the world. However as technology becomes more advanced and adaptable in identifying sexual trafficking, traffickers will find other means to advertise and exploit their victims. Despite efforts from governments and NGOs, the number of people in slavery is rising each year. Due to crises such as the refugee crisis in Europe, there is a new stream of vulnerable people for traffickers to groom and exploit. Traffickers will always find a way to exploit and financially gain from their victims, and no amount of prosecutions will stop this. Human trafficking is a complex issue that has to be combated through education, awareness and the continued prosecution of traffickers.