The marginalisation of Indigenous American peoples has been practically commonplace in society since Columbus’ ‘discovery’ of America in 1492. In today’s America, where political correctness supposedly runs rampant and discourse on the subject of cultural appropriation seems to be at the forefront of every other media controversy, one should be hard pressed to find examples of subjugation towards tribal communities. However, this is not the case, as evidenced by the continual use of inaccurate stereotypes as collective representations of Native peoples utilised in costumes, all examples of media, and as mascots for sports teams. More recently, however, the infringement on Native American rights has been highlighted by the Dakota Access pipeline controversy.

The Dakota Access Pipeline is a proposed 1,172-mile pipeline to connect the oil fields of North Dakota to refineries in Illinois that would transport around 470,000 barrels of oil per day. According to the project website, which is run by the pipeline company Energy Transfer, the project “is committed to working with individual landowners to make accommodations, minimize disruptions, and achieve full restoration of impacted land.” This statement has been proven illegitimate not only by the evidence of the protest movement which now has participants hailing from nearly 100 different indigenous tribes, but also in the instance of many non-native farmers in Iowa. Such is the case of Cyndy Coppola, who was arrested on her own land for attempting to block Dakota Access trucks on October 15th. She is just one of several Iowa landowners whose land is being used for the pipeline despite the owner’s objections, with Energy Transfer citing ‘eminent domain’ in order to gain easements.

However, this is not the only instance in which the practices of this project faced backlash. The official project website also contains a claim about their commitment to safety, stating “Underground pipelines are the safest mode of transporting crude oil.” However, according to data from the Federal Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, since 1986 an equivalent of 200 barrels of oil per day has been spilled as a result of accidents involving faulty pipelines. Furthermore, an April report from The Associated Press states that three separate federal agencies wrote to the United States Army Corps of Engineers, the group who approved the pipeline’s construction, after carrying out what these agencies claim to be a faulty environmental assessment. These correspondences call into question the assessments of potential impact to the environment, namely Native American drinking water sources, in the case of a pipeline leak, as well as the adequacy of justifications in concluding that there would be no significant environmental impact, including that of sites containing historical value to affected Native American tribes. The latter point of contention is elaborated on in the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation’s Section 106 Regulation, which “requires Federal agencies to take into account the effects of their undertakings on historic properties” and “place major emphasis on consultation with Indian tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations.” The developers also tout themselves as champions of the local economy with their “creation of 8,000 to 12,000 local jobs during construction.” The issue with this is that, in the long run, once construction is completed, these jobs will disappear and once again local unemployment will rise. In reality, the number of permanent jobs created by this pipeline project will go no higher than 40.

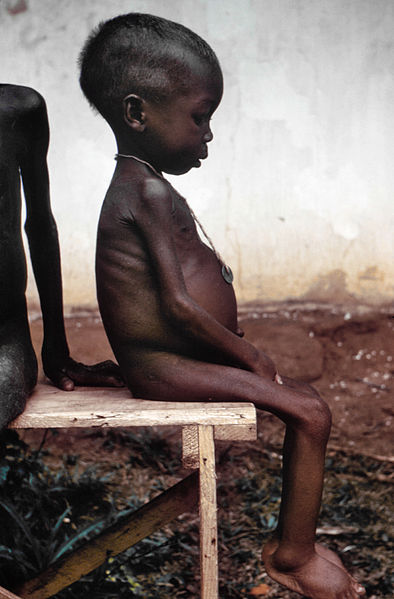

Tribal citizens demonstrating against pipeline construction

Since April of 2016, members and affiliates of various Native American tribes have protested the installation of the North Dakota access pipeline. Located on the outskirts of the Standing Rock Sioux reservation, the construction site for the pipeline, though not technically on the reservation, still cuts through what the Standing Rock Sioux consider to be ancestral lands, places where their forefathers once carried out day to day life. This land would have been inhabited or at least used as hunting grounds by Sioux people prior to the Treaty of Fort Laramie on April 29th, 1868, which corralled the once nomadic tribe for the personal gain of the United States government. From that point, lands of the Sioux Nation were repeatedly reduced, culminating in its division into six separate reservations in March 1889, thus forming the reservation of the Standing Rock Sioux.

In a September 23rd press release issued by Dave Archambault II, the Chairman of the Standing Rock Sioux, noted that they “have already seen the damage caused by a lack of consultation. The ancient burial sites where our Lakota and Dakota ancestors were laid to rest have been destroyed. The desecration of family graves is something that most people could never imagine… sacred places we have lost can never be replaced.” Mr Archambault’s statements serve as a testament to the grief felt not only by the Standing Rock Sioux, but by generations of indigenous peoples who have had their tribal lands disrespected or taken away completely throughout history at the hands of both the United States government and private companies alike.

The Dakota Access Pipeline under construction, by Lars Ploughmann

At the centre of this pipeline issue is a key component that is often overlooked, for lack of conceptual knowledge, the fact that it gets lost among the claims of the pipeline as primarily an environmental injustice, or due to general feelings of discomfort among those who have historically perpetuated racial injustices. This is the complex notion of tribal sovereignty, the inherent concept which, when recognised, allows for the self-determination of Native peoples. The DAPL is a project that, at surface value, may appear to be a racial group banding together in order to make an environmental complaint against a private company. However, this controversy runs much deeper than that, serving first and foremost as an exercise in tribal sovereignty, voicing a significant assertion about Native American self-determination in the face of a society which has systematically worked against them since the late 1400’s.

In the past week, tensions have risen between protesters and law enforcement officials, culminating in the arrests of at least 127 on October 22nd. There have been allegations from both sides claiming use of unnecessary aggression and unlawful tactics including unprovoked violence and pepper-spraying. Mr Archambault claims that “it is because of the behavior of the state that these tensions are heightened,” citing the use of blockades, police vans, and police in riot shields and the calling in of the National Guard by Governor Jack Dalrymple. These protests, which were intended to be peaceful acts of civil disobedience and often included prayer, have reached a boiling point as Energy Transfer continues with construction despite criticism from non-native activists, politicians, and celebrities alike.

The halting of the Dakota Access Pipeline construction would have a significance far beyond the context of this isolated event. It would serve as an acknowledgement of Native American rights and make a claim about tribal sovereignty that would hopefully bolster the exposure of injustices towards Native peoples and allow them the visibility which they should have inherently received for hundreds of years. In order to aid not only the Standing Rock Sioux, but indigenous peoples everywhere, donate directly to the Tribe through their website, sign a petition to President Obama started by Greenpeace, or send supplies to resistance camps.