In June 2016, Rifat Cetin was convicted and sentenced for insulting the President of Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. His crime? Posting pictures comparing Erdoğan to Gollum. He is not the only one to have noticed the similarity. Bilgin Ciftci, a doctor for Turkey’s public health service, also faced similar charges for posting memes which likened Erdoğan to Gollum. With a guile reminiscent of Gollum himself, Ciftci attempted to defend himself by arguing the Gollum was not evil but had instead simply been corrupted by power. In fact, he had a split personality, the corrupted Gollum and the innocent Sméagol. All the pictures Ciftci had used were of when Gollum was actually Sméagol, and therefore were not offensive. Peter Jackson, the director of the Lord of the Rings trilogy even waded in, arguing “Sméagol is a joyful, sweet, character. Smeagol does not lie, deceive, or attempt to manipulate others. He is not evil, conniving, or malicious – these personality traits belong to Gollum, who should never be confused with Sméagol. Sméagol would never dream of wielding power over those weaker than himself. He is not a bully. In fact he’s very loveable.”

Censorship on this level is absurd, but it can have a far more insidious and devastating reach. In August 2013, reporter Can Dündar was laid off by Milliyet, a Turkish daily newspaper after writing “too sharply” about the Gezi Park protests and Egypt. Dündar’s writing had displeased the then Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Not wishing to draw the ire of Erdoğan, the owners of the newspaper thought it was easier to fire Dündar instead.

Dündar quickly found new work as the editor-in-chief of Cumhuriyet, a left-leaning, up-market daily. Under his leadership Cumhuriyet won the Reporters Without Borders Media Prize for its “independent and courageous” reporting. Within weeks of winning the prize, Dündar and the Ankara bureau chief, Erdem Gül, were arrested on charges of membership of a terror organization, espionage, and revealing confidential documents. The charges were brought in relation to an article published in May 2015, which alleged that Turkish intelligence services had been sending weapons and ammunition to Islamist rebels fighting in Syria. Alongside the newspaper report there was a video showing police, who had stopped the trucks at the border, discovering crates of weapons hidden beneath boxes of medicine. The article and accompanying video angered Erdoğan, who was by this point President of Turkey, so much, that he proclaimed live on TV that “whoever wrote this story will pay a heavy price for this. I will not let him go unpunished.” They were subsequently convicted of publishing state secrets, with a sentence of 5 years and 10 months.

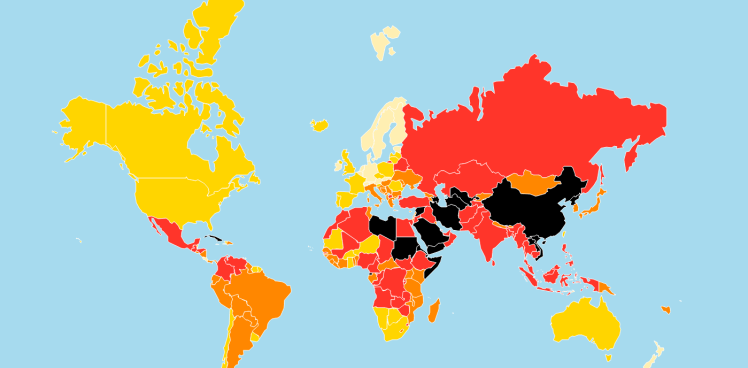

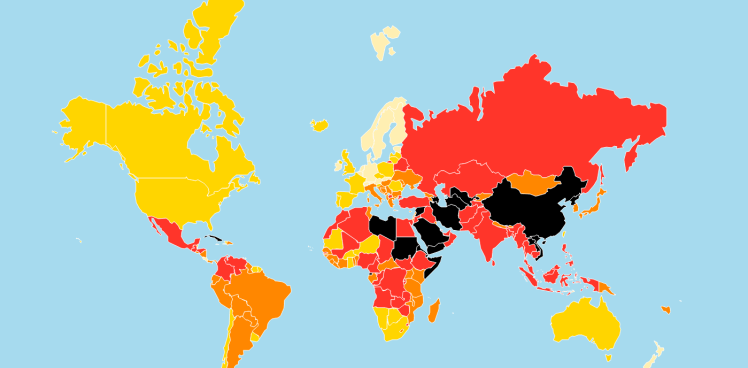

The World Press Freedom Index is an annual ranking of countries by their levels of press freedom. It evaluates media pluralism, media independence, media environment and self-censorship, legislative framework, transparency, the quality of the infrastructure that supports the production of news and information, and abuses and acts of violence against journalists. It is worth looking at a few examples, to see how this works in practice. Italy ranks 77th because a large proportion of the media is owned by former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, thus limiting pluralism, and the need for some journalists who report on organised crime to have police protection. The United States is ranked 41st, because whilst the first amendment protects media freedom, the government’s campaign against whistleblowers, and the lack of shield law on the federal level, which would allow reporters to refuse to testify about their sources, are held against them in the rankings. Uruguay is 20th, in part due to a 2014 law on broadcasting, that has been praised as being “exemplary” by the UN, for its encouragement of a pluralistic media, independent of the government. Finland was 1st, a position it has held since 2009.

A map of the world according to freedom of the press

In 2016, Turkey was ranked 151 out of 180 countries, flanked by Tajikistan at 150, and the Democratic Republic of Congo at 152. Turkey managed to score lower than Russia, which was 148th, and was described as having “draconian laws,” TV channels which “continue to inundate viewers with propaganda,” an “oppressive climate” for anyone who tries to question the new patriotic and neo-conservative discourse, or “just try to maintain quality journalism,” and who has declared many NGO’s to be foreign agents. To have such a low score requires a concerted campaign against a free and independent media. One does not get a lower score than Russia by simply being lackadaisical. It is a real achievement to be that oppressive.

In the first year and a half of Erdoğan’s presidency, 1,845 legal cases were opened against individuals who insulted the president. One case included a 13 year old boy who reportedly commented under a Facebook video that the president was “a son of a bitch”. In 2013, two Vice journalists were accused of “aiding a terrorist organisation”, for reporting on the fighting between Kurdish rebels and the Turkish military. In 2014 Twitter was banned, with Erdoğan declaring “we shall root out Twitter, I don’t care what the international community says, everyone will witness the power of the Turkish Republic”. This was part of the government’s response to the Gezi Park protests. Started in response to development plans for one of Istanbul’s few remaining green spaces, the protests morphed into a more general outcry on issues of environmentalism, police violence, freedom of speech, and new curbs on the sale of alcohol. The government passed a sweeping new internet regulation law, which gave the government the power to ban websites without judicial order and forced ISP’s to hold data on their users’ internet usage for two years and make it available to the authorities. In 2012 and 2013, more journalists ended up in prison in Turkey than in China or Iran, making Turkey the largest jailer of journalists on the planet. Arzu Yıldız was sentenced to 20 months in jail and deprived of legal guardianship of her children for publishing footage of a court hearing, at which four prosecutors were on trial for ordering a search of trucks belonging to Turkey’s National Intelligence Organization as they travelled to Syria in 2014. Erdoğan has claimed that the search of the trucks and some of the media coverage of it a plot by his political enemies designed to undermine him and embarrass Turkey. In March 2016, a Turkish court ruled that Zaman, Turkey’s largest daily newspaper was to be run by appointed trustees, due to its ‘terrorist activities.’ Within 48hrs, a paper which had been critical of Erdoğan and his government was publishing under a pro Erdoğan regime.

Erdoğan’s generosity, has however only stretched so far. Within three days of the recent attempted coup, 20 news portals were made inaccessible and the licences of 24 news and radio stations were cancelled. On June 27th, 12 days after the attempted coup, 102 media outlets were closed, including 45 newspapers, 23 radio stations, 16 TV channels, 15 magazines, and 3 news agencies. All were accused of being connected with US-based Turkish cleric Fethullah Gülen, who the authorities blame for the attempted coup, a claim for which they have yet to produce any evidence. Furthermore, 23 journalists were accused of being members of terrorist organisations, a charge which is used so often by the authorities against journalists, that it is becoming depressingly clichéd. They even arrested Erol Önderoglu, the representative for Reporters Without Borders in Turkey, on charges of terrorist propaganda after he wrote three articles about the conflict between the Kurds and the Turkish state. They subsequently released him after drawing global criticism, notably from the UN secretary-general Ban Ki-moon.

Yet why would the Turkish authorities follow such a course of action? Simply put, Erdoğan and the Justice and Development Party he founded are not democrats. They are Neo-Ottomans. Erdoğan perceives himself to be the heir of the House of Osman. He strives to be a strong, Islamic ruler. This is why he built himself a new presidential palace at the cost of $350 million, which included 1,150 rooms, 250 of which are for his own private residence. It is also why he is trying to build the world’s largest airport with six runways, when Heathrow, Europe’s busiest airport, manages with just two. Furthermore he has attempted to change the constitution to change the country from a parliamentary democracy, to a presidential democracy, concentrating power in the centre, although this may no longer be necessary given the power he wields during Turkey’s current state of emergency. This is not a question of if Islam and democracy are compatible, it is a question of Erdoğan’s authoritarianism and megalomania. This is clear in the case of Ahmet Davutoğlu, a man who served Erdoğan loyally for 15 years, first as a foreign policy advisor, then as foreign minister, and finally as prime minister when Erdoğan ascended to the presidency. Davutoğlu was backed by Erdoğan to be his puppet prime minister. However, when Davutoğlu started to err from Erdoğan’s path by dropping unpopular policies such as constitutional reform, and an aggressive approach towards the Kurds, Erdoğan ditched him without a second thought. Erdoğan did not care about the difficulties that Davutoğlu was facing, or that Davutoğlu might have opinions about the best way to proceed, he simply wanted him to obey orders without question. Erdoğan cannot seem to handle anybody, even his close allies and friends, hewing their own path and having their own opinions. He expects them to follow him at all times, in all things.

He is Erdoğan the Magnificent, and he cannot brook insult to the enormity of his magnificence. This is why he insists on prosecuting 13 year old boys who write mean things about him on Facebook, and doctors who post memes comparing him to Gollum. This is why he builds palaces to rival Versailles, in which he can live and work. He is a man who makes such statements as “It is alleged that the American continent was discovered by Columbus in 1492. In fact, Muslim sailors reached the American continent 314 years before Columbus, in 1178” and in response to the death of 301 miners, he blasély responded, “I went back in British history. Some 204 people died there after a mine collapsed in 1838. In 1866, 361 miners died in Britain. In an explosion in 1894, 290 people died there…These are usual things”.

Unfortunately Turkey is not alone in this. Reporters Without Borders notes in their World Press Freedom Index, that there has been a decline of 13.6% since 2013. In Egypt, Poland, and Hungary the same trend is occurring. Strong, central governments are curbing the power the free press in the name of security and public morality.

The erosion of press freedom, and the creation of an environment whereby a newspaper will fire a reporter for displeasing political leaders is a dangerous and worrying development for Turkey, and for the rest of the democratic world. President Obama once remarked that “a free press is a foundation for any democracy. We rely on journalists to explain and describe the actions of our government. If the government controls the journalists, then it’s very difficult for citizens to hold that government accountable.” Put simply, without a free media, there is no real democracy. Turkey seems to be erring towards being more sultanate than democracy, at the cost of it’s basic rights, and the dignity of its’ citizens.