A spray-painted swastika and the words: “We’ll get you all” deface the door to the home of seven Eritrean refugees just days before one, Khaled Idris Bahray, is found stabbed to death in his own courtyard. In Dearborn, Michigan, on February 12th, an Arab family is attacked after being called “terrorists” and ordered to “go back to [their] country.”

Xenophobia, the unreasonable fear or hatred of foreigners, is sowing terror in the lives of immigrants and refugees everywhere. Through increased coverage of Islamic extremists, notably the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), Islamophobia has intensified exponentially. According to a study by LifeWay Research, around 1 in 4 Americans now believe that ISIL is representative of the true nature of Islam. They view the highly publicized executions, suicide bombings, and anti-Western rallies as indicative of the attitude of all Muslims, without recognizing that extremists exposed in the media are there precisely because they are atypical. The sensationalist slant employed by the international media, in conjunction with widespread ignorance of Islam, have created an environment in which the response to terror is terror.

The ever-increasing percentage of the population that equate all Muslims with ISIL have tended to retaliate strongly. In Houston, Texas, the Quba Islamic Institute was set ablaze last Friday with supportive responses such as “let it burn…block the fire hydrant”, proliferating on social media.

Similarly, three students at the University of North Carolina were shot, execution style, last Tuesday, in an attack that family members and friends have labeled a hate crime. Although the attacker claimed that the crime related to a dispute over parking, his feelings towards Muslims were well known by neighbors.

Some Americans, it has also been argued, view foreigners as a threat to their way of life. Despite the fact that there have not been attempts to impose Sharia law in the US, more than a third of Americans have expressed concern about the possibility of Sharia law being integrated into judicial systems. Thirty-two states have already passed laws against this eventuality, in response to fears.

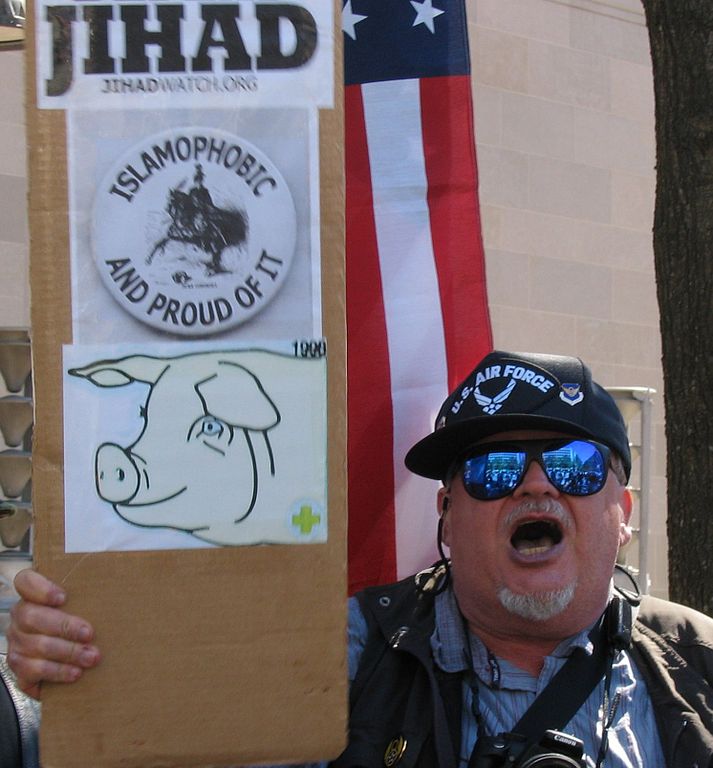

Anti-Islamic groups have used highly publicized ISIL attacks to garner support. The active anti-Muslim organization, American Freedom and Defence Initiative, spent 100,000 USD in October to run anti-Muslim ads on New York buses and in subway entrances. One of the ads depicted the execution of James Foley with a caption that read, “Yesterday’s moderate, is today’s headline.” This type of sensationalist propaganda not only incites fear, but also evokes painful memories for those who have lost loved ones in the battle against ISIL. Using the term “moderate” places all Muslims into an unfounded spectrum at the end of which is extremism. Consequently, ordinary Muslims are not sufficiently distinguished from the anti-Western acts of their radical counterparts. Grassroots anti-Islam movements, coupled with perpetual coverage of ISIL’s crimes, have resulted in anti-Islamic sentiment that has created an atmosphere of fear.

It is not only reporting on ISIL, however, that produces this negative outcome. Every September, Americans are reminded “never to forget” the attacks of 9/11. What is often ignored is that “never forgetting” also requires them to recall the animosity that was created, the tension against Muslims, and the insatiable urge to act even if it meant years of war and bloodshed.

In Europe, protests organized by PEGIDA (Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamization of the Occident), an organization that began as a small gathering of 350 people, peaked at a record high of 25,000 demonstrators on January 12th. Fortunately, other Europeans appeared to recognize the fear-mongering nature of these protests, with more than 100,000 counter-demonstrations taking place across Germany the next day. Similarly, many news stations have been quick to report on the anti-hate protests taking place in Europe. It remains easier, however, to find reports on ISIL’s horrific violence, than on the opposition of everyday Muslims to the crimes of this group. This approach silences the voices of those Muslims who are trying to explain that their religion is one of peace, rather than the hate and violence that is carried out in their name.

Last year, a mass grave comprised of Yazidis (formed of mostly Arabs), was found in the Kurdish region of Iraq. On February 16th, ISIL murdered twenty-one Egyptians. Sixty Muslims were killed in an ISIL bombing against a Shia mosque in Pakistan. Underreporting these stories serves to perpetuate the association of Muslims with ISIL and incites outrage by focusing on ISIL’s attacks against Westerners and Christians, even though the vast majority of their victims are Muslim and Arab.

Gordon Duff, an analyst on the region, has stated that by reinforcing the division between Shias and Sunnis, ISIL is attempting to destroy the Iraqi economy. Despite their devastating attacks, and the serious economic toll they are taking on Iraq and Syria, the beheadings of Americans, James Foley and Steven Sotloff, and British citizen, David Haines, remain some of the most exposed moments of ISIL’s campaign. ISIL’s heinous acts against Muslims and Arabs in the region are often ignored due to the intense focus on their anti-Western objectives.

This unbalanced reporting has contributed to the anti-Islamic hysteria that is sweeping across Europe and America. ISILs extreme violence remains inexcusable as does the backlash that has been experienced by Muslims and Arabs. Violence begetting violence still leads to a human rights violation, even if these stories are underreported. Targeting a specific group based on the perceived connection they have with another group, is similar to the rationale used by ISIL. The words, “We’ll get you all” reflect an individual-based sort of genocidal outlook. Those who connect Arabs and Muslims with ISIL efface them of their individuality and dehumanize them by associating them with the inhumane actions of ISIL. This kind of in-group out-group mentality can lead to ever increasing levels of violence if they are not sufficiently contained by attempting to understand and attempting to combat detrimental generalizations.