Ever since its independence from Sudan in 2011, the newly formed state of South Sudan has faced social, political and economic instability despite the efforts of countless forms of humanitarian aid and support. Earlier this year, the United Nations declared famine in parts of war-torn South Sudan where around 100,000 people face starvation and millions could die if something was not done. The UN is calling this the “worst hunger catastrophe” since civil war erupted there three years ago.

South Sudan’s President Salva Kirr issued an urgent appeal on April 4th of this year for international and regional aid: “I passionately desire to share with each and every one of you that once more our country is struck yet again by another national challenge, that of famine and poverty,” he stated.

The question we all need to be asking ourselves is how is it that, in 2017, people cannot find food, that people are dying because there is not enough to go around, that we as a global population cannot find a solution to ensure that everyone is given the basic human right: access to food? We now live in a world where we can order food through our phones, where supermarkets deliver to our houses and where unwanted food is simply thrown out. However, by just googling ‘South Sudan’ you can see that this privilege is not the case everywhere.

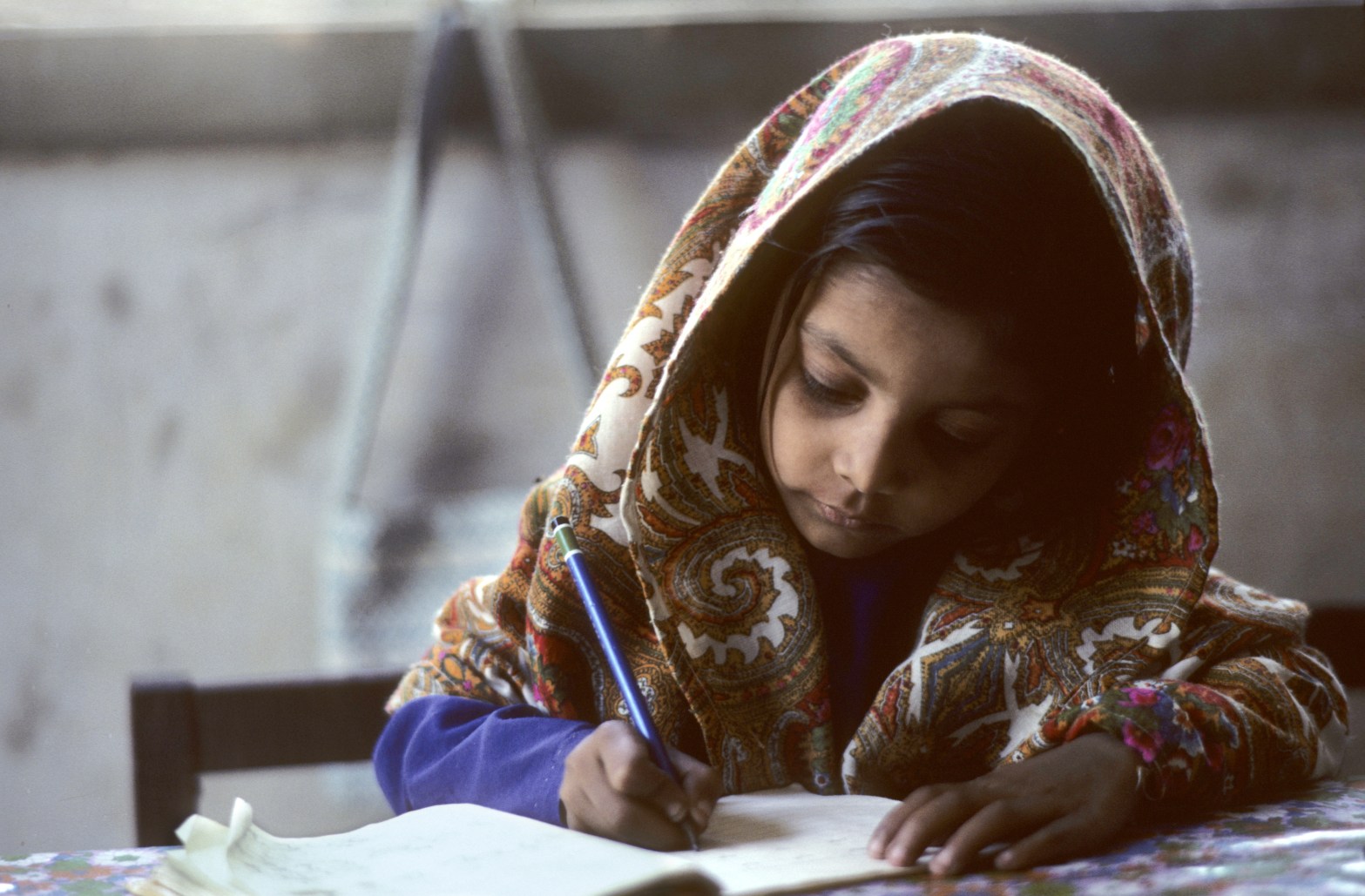

A South Sudanese man receiving a food distribution from Oxfam in March 2017, by Oxfam

The country has been at war since 2013 and more than 3 million people have been forced to flee their homes. Currently, some 4,000 South Sudanese cross the border to Uganda every day. The conflict in 2013 began when soldiers loyal to President Salva Kiir, a Dinka, and those loyal to former Vice President Riek Machar, a Nuer and now rebel leader, fought in the capital, Juba, following months of growing political tensions. Tens of thousands of people have died since then and the UN warns that South Sudan is at risk of genocide.

Last month, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres accused the government of South Sudan of refusing to express any meaningful concern about those affected by the famine, the 7.5 million in need of humanitarian assistance, and the thousands more fleeing due to insecurity. The government has been living in a state of denial hoping that the situation would change, but the food crisis in Sudan has reached a point of no return.

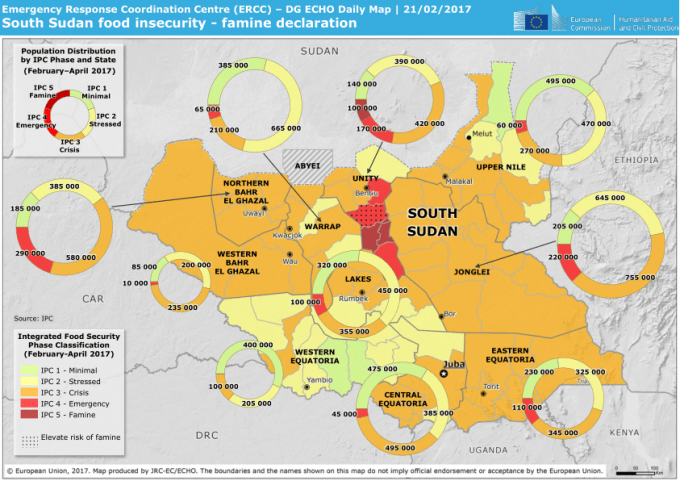

The most affected area in South Sudan is parts of the former Unity state, sometimes known as Western Upper Nile. The former state has been a site of continuous fighting throughout the civil war because of its vast oil resources as well as being a predominantly Nuer state which has faced attack from the Dinka’s during the war. The UN also warned that the famine would spread rapidly if no action is taken.

To add to their troubles, South Sudan’s widespread hunger has been accompanied by an economic crisis. The country is experiencing high inflation and the value of the currency has plummeted 800% in the last year, which has made whatever food that is available unaffordable for many families.

Not only have thousands died over the course of this crisis, but no serious efforts have been made by either side to make peace. The famine in South Sudan shows the failure of a government, the failure of opposition forces, the failure of peace negotiators, and the failure of the international community to take action and change the fate of the South Sudan.

UN officials have debated that hunger in South Sudan is even more alarming because of the country’s fertile land conditions and climate. Despite the fact that Sudan has the resources and climate to feed itself, corruption, lack of transparency, and the constraints placed on the delivery of food aid have left the country in ruin.

This is not the first time we have heard of famine in South Sudan: in 1998 more than 70,000 people died from starvation. However, a UN official blames politicians for the current food crisis. In a speech from the chair of the Commission on Humans Rights in South Sudan to the Human Rights Council it was mentioned that the opposition and the armed groups allied to them also contribute to the famine. They attack government property, steal convoys, and terrorise communities suspected of supporting the government or the Dinka tribe.

The speech affirms that it is essential to look at the famine from a human rights perspective. If the government of South Sudan continues to deny humanitarians access to opposition-controlled areas hit by famine, we shall be faced with an even greater problem.

So, the answer to the question above is simple: the famine in South Sudan is man-made, it is due to the terrible actions of those initiating and encouraging war but also due to the inaction of the international community. Inaction from me, you, and us as the global community.

Can you imagine having a family and not knowing where your next meal was coming from? or knowing that it was not coming at all? The total number of food insecure people is expected to rise to 5.5 million by July if nothing is done to ensure the proper access of humanitarian aid. We cannot sit idly by and watch this happen. We have an obligation to try and implement change.

South Sudan Food Insecurity – Famine Declaration, from the ERCC

South Sudan has been in the news for years, the cycle is endless: war, famine, death. Whichever way a story is narrated the problem remains the same. What needs to change is the response.

As Ban Ki-Moon once said, “as the young leaders of tomorrow, you have the passion and energy and commitment to make a difference… have a global vision. Go beyond your country; go beyond your national boundaries.” If you want to learn more about the conflict and famine in South Sudan or wish to donate to save a life, the Human Rights Watch has the latest on the conflict.