Cash-for-sterilisation. It’s an idea that took me a while to get my head around, despite the fact that it really is as simple as it sounds. Established in 1997 by Barbara Harris, Project Prevention tours States and cities across America (recently expanding overseas), touting one simple message: “Don’t let a pregnancy ruin your drug habit”.

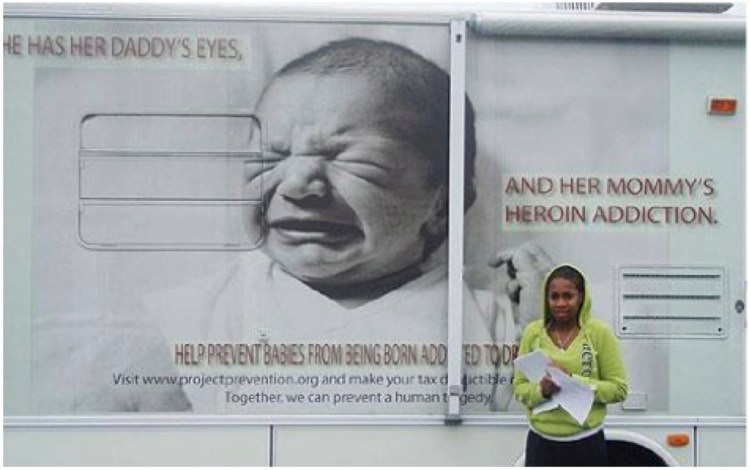

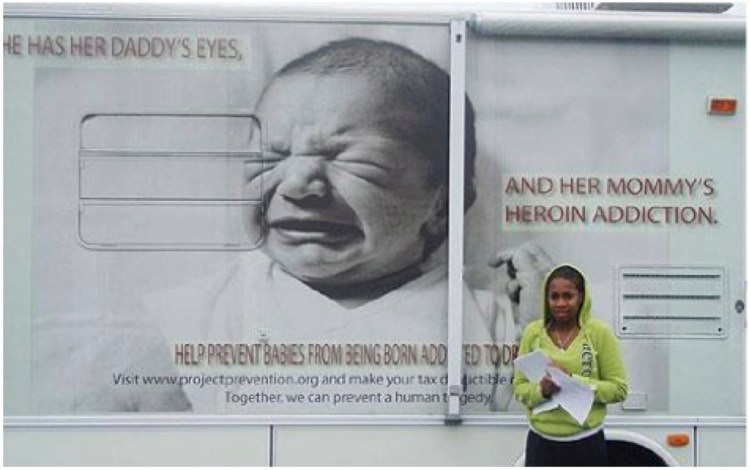

So far, the organisation has sterilised or given long-term contraception to over 4,000 individuals, the vast majority of which are women, in exchange for $300 US dollars. Their advertising campaign is far from glamorous; volunteers hand out flyers to unsuspecting individuals in areas notorious for poverty and drug use, stick notices in AA/NA groups and travel the country in a large bus bearing their unapologetic posters with the number 1-888-30-CRACK, urging any fertile individual suffering from alcoholism or drug addiction to get in touch.

Conceiving Project Prevention

Over twenty years ago, mother of 6 boys Barbara Harris and her husband adopted a baby girl- Destiny. They discovered that their new daughter was suffering from withdrawal symptoms as a result of her birth mother’s drug addiction and, over the course of the following years, adopted 3 further children born to the same drug addicted mother. At the time they were told that their daughter might suffer developmental problems, however she has since gone on to prove a success academically, obtaining a place on the Dean’s list of the college she attends.

This experienced enlightened Barbara to the difficulties associated with raising children born to drug addicted parents, and she quickly set about finding a solution to this problem. After failing to pass a Bill (the Prenatal Neglect Act) in her then State of California, she founded Project Prevention to tackle this problem at a grass roots level1. The aim of the program is clear; to stop individuals suffering from drug addictions having children, as put by Harris: “If I had enough money there wouldn’t be any pregnancies for drug addicts”.

However, where her bus travels, controversy is never far from its tracks- with many human and civil rights organisations citing the program as irresponsible, exploitative and far too close to eugenics than we should be willing to tolerate. Before making your standpoint on this issue however, let’s have a look at what it is exactly that the project is aiming to prevent.

Preventing In Vitro Child Abuse?

Let’s be under no illusion here. Alcohol and drug use during pregnancy is not recommended and has the potential to lead to a number of damaging effects on the foetus or newborn. These include miscarriage, premature labour and developmental delay. However, as exemplified by the academic success of Barbara Harris’s own adopted daughter, these effects are variable and may be altered by many factors both prenatal (the extent of drug use, stage of pregnancy and type of drug taken) and postnatal (nutrition, attention and stability of the child’s environment.).

Those who support the program on the basis that it is not fair to cause preventable damage to an unborn child face a number of problems. Firstly, the argument is weakened by the fact that it is not possible to predict the extent to which these substances will act as teratogens. With a minimum chance of 4-5% that the baby will develop a major birth defect, it is indeed possible that a baby might be born completely healthy.

Furthermore, to normalise sterilisation with the desire to protect against disability is to say that these traits are undesirable to the extent that they render a life not worth living. This implies that those living with disabilities are in some way inferior to their “healthy” able-bodied counterparts, risking the marginalisation of these individuals in society. Similar problems have been found in implementing the criteria for abortion- where having a child with a disability has been cited as a reason to abort.

Preventing Cruelty to Children?

Children who are raised in families with parents as drug addicts are more likely to suffer from malnutrition and are2-3x more likely to suffer abuse or neglect, if they have been exposed to drugs prenatally. Far too often stories of children suffering unimaginable abuse at the hands of their own parents appear in the news. A particularly tragic story is from 2010 and is that of the death of Maggie-May, a 10-day-old girl who died after being placed in the washing machine by her mother, an established drug addict.

Preventable incidents like this are almost impossible to comprehend, and in light of this many people may rush to support sterilisations in an attempt to prevent any future tragedies. This reaction is understandable; however what these stories should highlight is failings in the safeguarding of children and there are many alternatives to the sterilisations proposed by Project Prevention that are developed and currently in use. Instead this highlights failings in society to intervene and help struggling families and suffering children as necessary. As has been commented by an opponent of the program in the discussions section of an article about Project Prevention, “Some people may not deserve to have children, but those children deserve to be born”, and it is our job to protect these children.

Harris has argued that to have a child born into a drug addicted environment is to deny them a normal life. Yet to suggest that a “normal” life is required for an optimal childhood (and hence a better person) is to believe that one can dictate what a normal childhood should be. This goes beyond the use of drugs by parents, and challenges all circumstances that might possibly influence the raising of a child. If this idea is supported, does it follow that we must sterilise individuals who are less wealthy, or homeless, disabled, unattractive, overweight or those who have a low IQ, purely to maximise the chances of having a “normal child”?

What does it cost us?

Aside from the ethical issues, such as those discussed above, the economic cost to society should not be forgotten. The social and health costs required to care for a baby born with drug addictions are high, with it costing approximately $500,000 alone to wean a methadone-addicted baby off the drug. Project Prevention has raised (using very modest estimates) at least 1 million dollars in their US program alone. This amount would only have been sufficient to care for 2 babies- $300 looks a small price to pay compared to the princes ransom required should a birth go ahead.

There is an undeniable cost, economic and emotional, associated with caring for babies born to drug addicted parents, and this cannot be ignored. We must therefore act with responsibility, recognising that the burden on society is substantial. However this cost is surely what we must be willing to pay if we are to live in a world where the life of a baby born into the most disadvantaged of circumstances is given the same inherent value as that of a baby born into the most privileged of environments.

Preventing making mistakes?

Finally, there are those who will say that paying individuals to halt- either permanently or temporarily- their reproductive capacity is beneficial to the person themselves. It enables individuals, women especially who would have to take on the responsibility of a pregnancy, the opportunity to evaluate whether they are ready to have a baby before they fall pregnant. They can decide for themselves how their circumstances will be affected by the responsibility of raising a child and may come to the conclusion that they need to address their own addiction before having a baby.

This would have the advantage of avoiding situations where a mother is separated from her children- an experience that is unbearably painful to witness, let alone experience. In addition, costs to society for raising a child placed into care are eliminated. It would seem therefore that having the opportunity to choose long-term contraception (as Project Prevention provides) is a wonderful solution. So how can we find a fault in it? If someone has decided that they do not wish to have children, what gives anyone the right to say they cannot make this decision-surely we must support Project Prevention?

Coming to this conclusion however is to succumb to the most tantalising of all the reasons given in defence of Project Preventions existence- that it is voluntary.

Consent: Can it ever be informed?

This claim to be voluntary may have been true if there was no financial incentive to undergo the procedures, however as soon as money is brought into the arrangement we must question how free the choice really can be. After all, would a wealthy drug addict, not in need of the money, take up the offer? And what might someone in desperate need of money be willing to do for $300? You may find yourself reaching the same conclusion that I did- that this transaction acts as nothing more than a thinly veiled exploitation of individuals who are at their lowest ebb.

In the UK, informed consent is a prerequisite for any adult about to undergo a medical procedure. In order to give informed consent, an individual must be able to give a decision that is informed, voluntary and with capacity.Harris’s program would rarely fulfil all three criteria, and ensuring that it does is impossible.

In order to establish whether the decision is informed, we must come to an agreement on how much information a patient would need to make a fair decision. Is it only the technical details that they require, or must we also inform them of the array of possible emotional and social consequences that they may face as a result of electing to postpone or halt their reproductive potential? If we are to include the latter then we must accept that the decision could never be fully informed, as it is impossible to predict with accuracy the long-term impact of this process on a person. Finally, it is an individual’s eligibility for the program (that of being a drug addict) that calls their capacity to make a decision into question. Can we really say that someone who is under the influence of drugs has the capacity to make a life-changing decision?

In response to this last point, Harris argues that if we say a woman is not in her right frame of mind to elect for sterilisation (i.e. cannot give informed consent), she cannot be in the right frame of mind to have a baby and therefore this decision should be made for her. Indeed, making decisions for individuals lacking in capacity is necessary in some cases and is legalised in the Mental Capacity Act 2005. This act aims to protect vulnerable individuals and stipulates that any decision made on behalf of a patient must be made in the best interest of the individuals themselves. Project Prevention on the other hand is held to no such restrictions and acts with the interests of the potential foetus and society at the forefront of its decisions – with the rights of the drug user themselves a disposable consideration.

The true cost of $300

The low value of the monetary incentive means that the system disproportionately affects the poor- further calling into question whether those entering the program really do have freedom of choice. For some, the decision to enter the program may occur as a result of evaluating sterilisation as the better of two evils. It is difficult to argue that a health decision has been made freely if an individual is in desperate need of the money-even if it is ultimately to supplement their addiction. As we shall see shortly, in Kenya (a country where 46% of people live below the poverty line) Harris is developing a similar program targeting women who are HIV-positive- it is clear that for these women a financial incentive may hold even more of a bearing on their decision.

For some, perhaps the payment is nothing more than what it claims to be- an incentive to get individuals seriously thinking about their suitability as parents and deciding whether this is something that they want to become. For most however, the monetary reward carries much more weight than the paper it is written on. It is the means by which a drug addict may get their hit, an opportunity for unscrupulous individuals to manipulate or exploit vulnerable addicts and, most dangerously, the money acts as the tool for which a person (usually a woman) transforms their reproductive potential into a commodity.

By condoning these practices (purely by enabling their existence) we are treating individuals as though they are tainted, and have no desirable traits to pass on to the future. This robs individuals of their vitality; those who may have been wonderful parents are not only prevented from becoming so but also brain washed into believing that they should not aspire to be so either. Instead of offering these individuals the help they need, we are reinforcing stereotypes that they are not welcome in society, and simply giving up on them.

Project Prevention overseas

UK: In 2010 Barbara started her expansion overseas, setting up camp here in the UK. Unlike in America however, the project garnered very little support. So much so that pressure from the BMA has meant that the UK branch is unable to offer money in exchange for sterilisation (with only long term contraception being offered for money) andonly 31 individuals have entered the UK program to date. In a country such as the UK with an NHS that offers free contraception to all the money offered to drug abusing individuals looks far less like an incentive, and a lot more like a bribe.

Kenya: One of the latest moves of Project Prevention has been to target poverty-stricken families in Kenya- offering sterilisation to HIV positive women in exchange for 40 US$. In this scheme, Project Prevention have taken the rose-tinted spectacles away and revealed its true eugenic aims. For some reason they haven’t got the message that HIV is no longer a death sentence, and that there is effective prophylactic treatment (WHO guidelinesrecommend the antiretroviral drug Zidovudine (AZT)) available that women can take during pregnancy.

The project is targeting women exclusively and could be perpetuating local stereotypes that HIV positive women (and oftentimes women in general) are inferior, “unclean” members of society who are responsible for the prevalence of the disease. In a culture where a woman’s vitality is an important part of social standing, to take this away for $40 US dollars is an unbelievable shame.

Conclusion

Previously, I have described Project Prevention as being ‘simply wrong’, as it turns out however, there is nothing simple about it. It is an ethically reprehensible and morally bankrupt scheme. And yet still, it exists. Why? Perhaps because rather then address the underlying problems in society-failings in the provision and appropriate delivery of social care, failure in preventing drug distribution and unsuccessful or overworked drug rehabilitation schemes to name a few, it is much easier to stick plaster over the issue and hope it disappears.

Of course, accepting the coercion of vulnerable people to make life-changing decisions comes at a cost; and in our apathy to its existence we are actively sacrificing our morality for our money. Electing for a eugenic approach to solving complicated social issues could lead us to a future that echoes the horror associated with Nazi era eugenics- and we could find ourselves getting there much more easily then we would dare to imagine.