Third Generation Project (TGP) is an innovative think-tank, based in the School of International Relations at the University of St Andrews. TGP exists to collaboratively advocate and promote the collective rights of communities, in particular those who are on the frontlines of climate change. Human rights function on three levels. Primary and secondary rights form the main focus of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), whose adoption we are celebrating this week. These levels (or generations) of rights cover individual civil, social and economic rights, such as freedom of speech, equality before the law and the right to food, housing, and employment in just and favourable conditions. Tertiary – also known as third generation – human rights go beyond these individual rights to cover the collective, and include the right to a healthy environment, the right to participate in cultural heritage and the right to self-determination. Collective rights are not explicitly denoted in the UDHR and whilst initial steps have been taken to recognise them, the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights remain the only two statutes which enshrine the need to protect communities in international law. TGP believes that collective rights are as important as individual ones, and that the former – in particular as regards communities’ social and environmental collective rights which are often impacted by climate change – are neglected. We work to redress this neglect by building bridges, through action and research, between affected communities, policy-makers, scholars and activists. We seek to work with and for affected communities to promote specifically their knowledge and concerns among the upper echelons of political decision-making.

In the following paragraphs, TGP’s student research interns will introduce a range of issues TGP and the collaborating communities grapple with – spanning from corporate and state accountability, to land and water rights, and to climate refugees and displaced peoples. First, we shall present research on the US government’s efforts towards including environmental and Indigenous activists under counter-terrorism legislation. Then we shall review TGP’s collaboration with AIMPO (a grassroots organisation in Rwanda) to reduce Twa land and food poverty, aggravated by government-led evictions. The final two paragraphs shall examine small-island-states, first illustrating some of the challenges they face regarding climate change, such as ‘climate refugees’ and rising sea levels, then introducing the approach and action taken by Fiji, as the leader of this year’s COP23 climate talks, to encourage international collaboration regarding climate change through placing particular emphasis on Pacific experiences.

Source: Flickr.

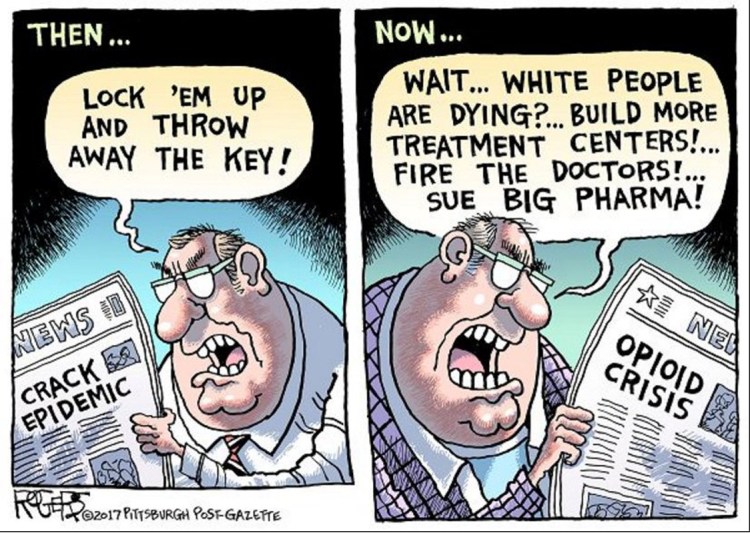

Protests Around the Pipelines – Tyler Tsay

TGP has been tracking the use of counter-terrorism legislation in the arrests of Indigenous and environmental activists at the Keystone XL Pipeline, Standing Rock and other areas. This research begins with a letter sent from Congresspeople to Attorney General, Jeff Sessions, asking whether the Patriot Act could be used to prosecute water protectors or environmental activists; it also asks whether pipeline protesters could be classified and tried as domestic terrorists. The letter symbolizes the culmination of years of domestic legislation that has allowed the near outlaw of environmental protest in the name of Indigenous peoples. For the first time since the civil rights movement, environmental activists, either of Indigenous descent or working closely with Indigenous leaders, have regularly been charged under “civil disobedience” and counter-terrorism statutes that have historically been weaponized by police against minorities fighting for basic human rights. Contemporary prejudice from U.S. representatives and judges have set the foundations for a government that forbids peaceful protest from its citizens, particularly when the matter regards Indigenous lands, rights and cultural/religious protections. The broadening scope of counter-terrorism legislation has increasingly permitted the American government, and governments around the world, to infringe upon human rights under the guise of protection and environmental safety. Federal workers and troops around the pipeline projects, for instance, continually use excessive force against activists and exercise dominion over the area “at all costs” as dictated by President Trump’s executive order on Keystone XL. As the Trump administration continues to unravel the legacy of the previous administration’s environmental policy, TGP will examine the documents, precedents and codifications that have legalized centuries of state violence against minorities, Indigenous populations, queer peoples and others, evidenced by the unlawful arrests of water protectors and activists. TGP hopes that this research, along with its other work, will add to the knowledge that Indigenous activists can use in the fight against climate change and state violence.

TGP collaboration with the Twa, the Indigenous Peoples of Rwanda – Annabelle von Moltke

As demonstrated above, TGP works closely with grassroots organisations to support and contribute to these organisations’ efforts to defend their communities’ collective human rights. A further example of such collaboration would be the TGP’s partnership with the African Initiative for Mankind Progress Organisation (AIMPO). AIMPO is one of two non-governmental organisations in Rwanda working to advocate for the human rights of ‘Historically Marginalized Peoples’, previously known as ‘Twa’, to alleviate some of the population’s pervasive concerns, such as lack of food security, land scarcity, low levels of education and high levels of gender-based violence. The Twa are recognized internationally as Rwanda’s Indigenous Peoples, yet are not legally recognised as such by the state, despite Rwanda’s technical support of the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and in defiance of repeated UN condemnation. In the wake of the Rwandan genocide (1994), the government have chosen to orchestrate ‘ethnic amnesia’, focusing instead on the construction of Rwandan civic identity (Vandeginste 2013). The Twa are now classed as “Historically Marginalised Peoples” – people who have been “left behind by history” – an ambiguous label which most civil society organizations also believe includes disabled people, women and Muslims (Collins and Ntakirutimana 2017). This erasure of ethnicity from public and political discourse and the introduction of this blanket category, obscures the discrimination faced by the Twa, and makes differentiated data collection as well as human rights advocacy practically difficult and politically sensitive. An example of the injustices suffered specifically by the Twa is their expulsion from their ancestral forest homelands over the course of several decades as a result of deforestation, conflict leading to forced displacement, natural resource extraction, and conservation in the name of development. TGP and AIMPO’s current collaboration seeks to collate knowledge of Twa resources and experiences for their own use, in particular to strengthen their platform for advocating their communal rights, a process which aims to ultimately increase Twa access to land and reduce food insecurity. At TGP I have helped with the first stages of applying for funding for AIMPO-TGP projects from the European Commission, a regional/supranational organisation. From an analytical perspective, this is also an interesting example of how human rights legislation shapes interactions between non-state and supra-state organisations and how these norms are made meaningful on a local as well as an international level.

Climate Refugees and Small-Island Developing States – Yasmine Maize

As TGP promotes the collective rights of communities, the threats that climate change poses to many communities’ rights is examined and discussed. People who have lost their homes and are forced to move due to unliveable conditions or environmental disasters caused by climate change have become known as ‘climate refugees’ (UNHCR). However, the 1951 Geneva Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees defines “refugees” as people who have been forced to leave their country and cannot return home safely due to war, persecution or conflict. Due to this legal incompatibility between the international definition of ‘refugee’ and the refugee-like position that ‘climate refugees’ face, there is a legal gap that leaves communities suffering from climate change without any international legal status. Refugees created by political issues are protected from being returned to the danger in their country and are given access to fair asylum procedures; yet climate refugees only receive help in “extenuating circumstances” in which the UNHCR deploys emergency teams to provide concrete support in terms of “registration, documentation, family reunification and the provision of shelter, basic hygiene and nutrition” (UNHCR). This type of assistance is very limited, which leaves climate refugees particularly vulnerable. Due to the fact that the majority of people displaced by disasters and climate change remain within their own borders where the individual states have defined responsibility, the international community often does not focus on providing aid to these displaced communities even though there is extreme need.

Though many communities are impacted by climate change throughout the world, the impacts are especially concerning for Small-Island Developing States (SIDS). Since the 1994 United Nations Conference in Barbados, SIDS have gained international attention, especially pertaining to the issue of sea level rise and the impacts of climate change. There are 39 SIDS, whose communities constitute about five percent of the global population (AOSIS), and are specifically islands of the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific Oceans (UNESCO). SIDS are particularly vulnerable to loss of land through sea-level rise due to their typically small-size and high-coastal proportion, and are also more susceptible to infrastructure damage by intense weather occurrences due to their isolated location. However, SIDS are often without sufficient economic or physical resources to address these climate-caused issues that they face. As much of the way of life for communities in SIDS is rooted in their specific islands, the threat that climate change poses jeopardizes many of their cultures, senses of identity, and lifestyles. In order to prevent these issues from augmenting, there is a pressing need for international action to alleviate the current hardships that communities face and to create a platform to address the future issues that are expected to arise from climate change. As stated in Article 43 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, the rights of indigenous people include their “survival, dignity and well-being” (2007). As all of these aspects are threatened by climate change, the need for the protection of these collective rights can be identified as internationally necessary. As TGP, we study the link between the need to protect the collective rights of communities and the conjoined need to address climate change.

Fiji as the Leader of COP23 – Tom Hurst

Fiji was chosen to lead the COP23 conference in Bonn this past November. The COP talks are forums – organised by the United Nations every two to three years – where member states congregated to discuss the challenges they face caused by climate change. This year, Fiji brought a new perspective to the table; it was the first small-island-state to be elected as leader of the conference. Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama made clear his desire to infuse the conference with Fiji’s ‘Bula Spirit’ of ‘inclusiveness, friendliness and solidarity’ (COP23: Fiji’s Vision for COP23). This was coupled with the guiding principle of ‘Talanoa’, ensuring ‘a process of inclusive, participatory and transparent dialogue that builds empathy and leads to decision making for the collective good’; this was recognised and praised by UNFCC Executive Secretary, Patricia Espinosa, before the conference took place. Bainimarama regularly mentioned his desire to make clear the need to draw a stronger link between the health of the world’s oceans and the impacts of and solutions to climate change, as part of a holistic approach to the protection of our planet. This, he feels will best be achieved through the forging of a grand coalition to accelerate climate action before 2020. This coalition, for Bainimarama has to be at all levels; ‘civil society, private sector and ordinary citizens’ in order to move ‘this agenda forward’ (COP23fj YouTube: Fijian Prime Minister addresses the 72nd Session of the UN General Assembly). The right to a healthy environment has been identified as a part of third generation human rights, and was at the forefront of the issues discussed as a Fijian schoolchild spoke at the conference, describing climate change as a ‘thief in the night’ (Radio New Zealand News: Fijian Students Speak at COP23). Bainimarama drew on his experience as ‘a Pacific Islander, who comes from a region of the world that is bearing the brunt of climate change’ (COP23: Fiji’s Vision for COP23), (caused primarily by overfishing, rising sea levels and the increasing number and intensity of freak weather events) to further the interests of the global population as well as those communities in small-island-states who are already feeling the catastrophic effects of global climate change.

In conclusion, this introduction to various TGP projects illustrates TGP’s commitment to addressing the effects of climate change on frontline communities, and the rights of underrepresented communities, as well as the ways in which these interact, through a combination of collaborative research and action. By raising awareness of the US government’s abuse of the Patriot Act, TGP works to support environmental and Indigenous activists in their struggle to protect their land and water rights. In collaborating with AIMPO, TGP is helping to facilitate engagement with state actors to redress structural discrimination against the Twa, which underlie many of their most pressing daily challenges. Finally, through research on the disproportionate impact of climate change on small-island-states and the underappreciated role island states play in shaping international negotiations, TGP seeks to highlight not only their concerns but also their knowledge, whose prioritisation is of fundamental importance in regards to approaching climate change and the collective human rights ramifications it has.