The notion that people are entitled to certain inalienable rights has long been a part of the fabric of international relations, in theory if often not in practice. However, the form that these rights should take is far from straightforward, with tensions and tradeoffs to be made between civil, political, social, and economic rights, and between the rights of individuals and collective rights. Our understanding of where these tradeoffs are to be made and which rights are prioritised over others is never a neutral process, but reflects implicit judgements on what, and by extension who, is considered valuable. The prevailing emphasis on individual over collective rights, and on civil and political over social and economic rights, is not a fundamental truth, but a reflection of liberal Western values that often go unexamined.

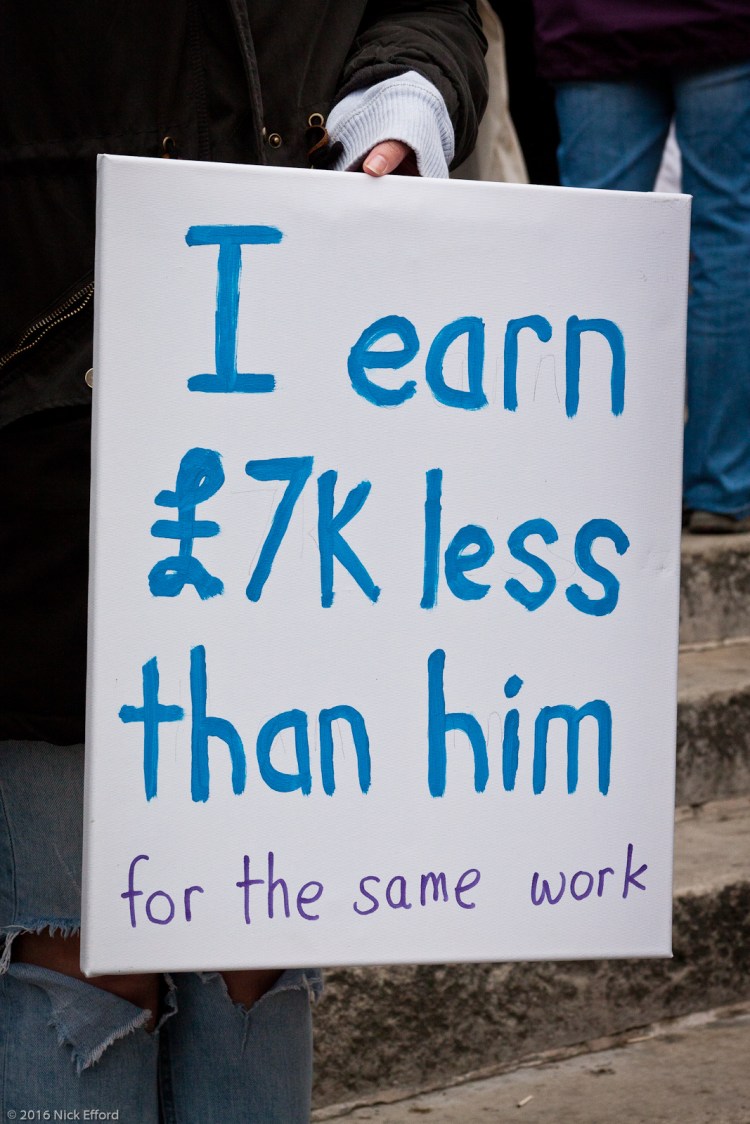

Our rights can be divided into three ‘generations’. The first generation of these is civil and political rights – to freedom of speech, to participation in public life, to due process before the law, and the human right to life. Broadly speaking, these rights are negatively defined, and protect us from excessive interference in our lives by the state. Freedom of speech, for example, is not an invitation to say anything, anywhere, regardless of context or consequences, but a guarantee against being arrested or persecuted for what one says. After the first generation of civil and political rights comes a second generation of social and economic rights – rights to things such as adequate food, housing, and healthcare. In other words, second generation rights maintain that individuals have a right not only to be free from persecution, but also to a basic quality of life. When we discuss human rights issues in the UK, we are most likely to think of the protection of civil and political rights against threats to press freedom, but we can also think of rising food insecurity as a social and economic human rights issue.

Economic rights are a relatively new addition to international aid efforts, which previously tended to focus on the right to life through basic healthcare and disaster management. Access to first and second generation rights is interrelated: those who are economically disenfranchised will also struggle to exercise their civil and political rights, with restricted access to due legal process, to the press, and to the political process.

The right to a clean environment is considered a collective right

The various rights included under the labels of ‘first’ and ‘second’ generation share commonalities; they are understood as accessed, restricted, or denied on an individual basis and are both addressed by the 1948 UN Declaration of Universal Human Rights. In fact, the idea that human rights can also be understood on a collective basis was not articulated by the UN until the 1970s, in recognition of the fact that rights to a clean environment, to peace and stability, or to self-determination cannot be divided between individuals, but are denied or realised on the level of the community. These rights are much less ingrained in traditional Western political discourse, where the individual or state overwhelmingly remain the primary point of reference.

Collective rights do, however, appear in a number of non-Western constitutions. Unsurprisingly, Communist regimes in Russia and China wrote collective rights into their constitutions. They also stressed social and economic rights over civil and political ones. These rights were also codified in the 1981 African Charter of Human and Peoples Rights, which guarantees “peoples” rights to equality, to self-determination, to development, as well as the rights to “freely dispose of their wealth and natural resources” to “peace and security” and to “a generally satisfactory environment.”

Western politics continues to resist this interpretation of human rights. One easy retaliation to collective rights is to point to the ease with which authoritarian regimes can use the importance of third generation, as well as second generation, rights to justify suppressing first generation rights. The self-determination of the group, defined of course by the state, the preservation of material welfare, and protection of stability are all easy pretexts for restricting individual freedom of speech or assembly.

However, the reverse is also true. The Western liberal focus on individual rights – more often on the civil and political than the social and economic – makes it easy to resist calls for systemic change and ignore marginalised groups. This is demonstrated most starkly in the case of indigenous peoples, who are among the world’s most disenfranchised, and who the prevailing regime of individualised human rights, both in international treaties and domestic legal systems, largely fails to address. Individual rights can only go so far to protect cultures and ways of life that dominant states have spent centuries disenfranchising and persecuting. Recognising collective rights both explicitly acknowledges this reality, and is a long overdue response to the measures for which many of these groups themselves have been campaigning.

Environmental degradation and economic disenfranchisement are suffered, as well as perpetrated, on a collective basis, but a focus on individual rights shifts the search for solutions away from this fact. Instead, it encourages us to see individuals in isolation, where the weight of history and structural oppression are easier to ignore. This makes it easier to see discrimination as something perpetrated by an individual against another individual, rather than a structural process enacted by one group upon another group. An effective shift towards respecting collective rights requires us to place more emphasis on listening to groups that have been sidelined by traditional structures of power and knowledge, in particular activists, communities, and other actors that do not necessarily speak the language of academia. It also represents a shift in emphasis in terms of what is valued, by placing greater value on social belonging and the prospering of communities – in other words a recognition of the damage done by social marginalisation, in addition to that of political and economic disenfranchisement.

The Third Generation Project, a St Andrews-based human rights think tank, is dedicated to challenging the dominance of unexamined narratives that underlie how we think about human rights and to reframing this discussion with a focus on collective rights. Through their advocacy and research, the Project aims to draw attention to groups, issues, and sources of knowledge that have traditionally been sidelined in Western academic and policy circles. With a particular focus on land and water rights of indigenous peoples in North America and East Africa, and by putting community-led action at the heart of what they do, they hope to bring traditionally marginalised voices into the centre of the study of human rights and international relations, as well as to to push our understanding of rights beyond individuals and towards the rights of groups and communities.

To find out more about the Third Generation Project, visit their website.