South Sudan is a nation in its infancy. Born in 2011 after decades of internal conflict whilst part of the Republic of Sudan, the country is mired in a civil war that has claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands. It is now faced by a further threat, resultant of the ethnic conflict it is embroiled in: a famine that risks the integrity of the state less than a decade into its existence.

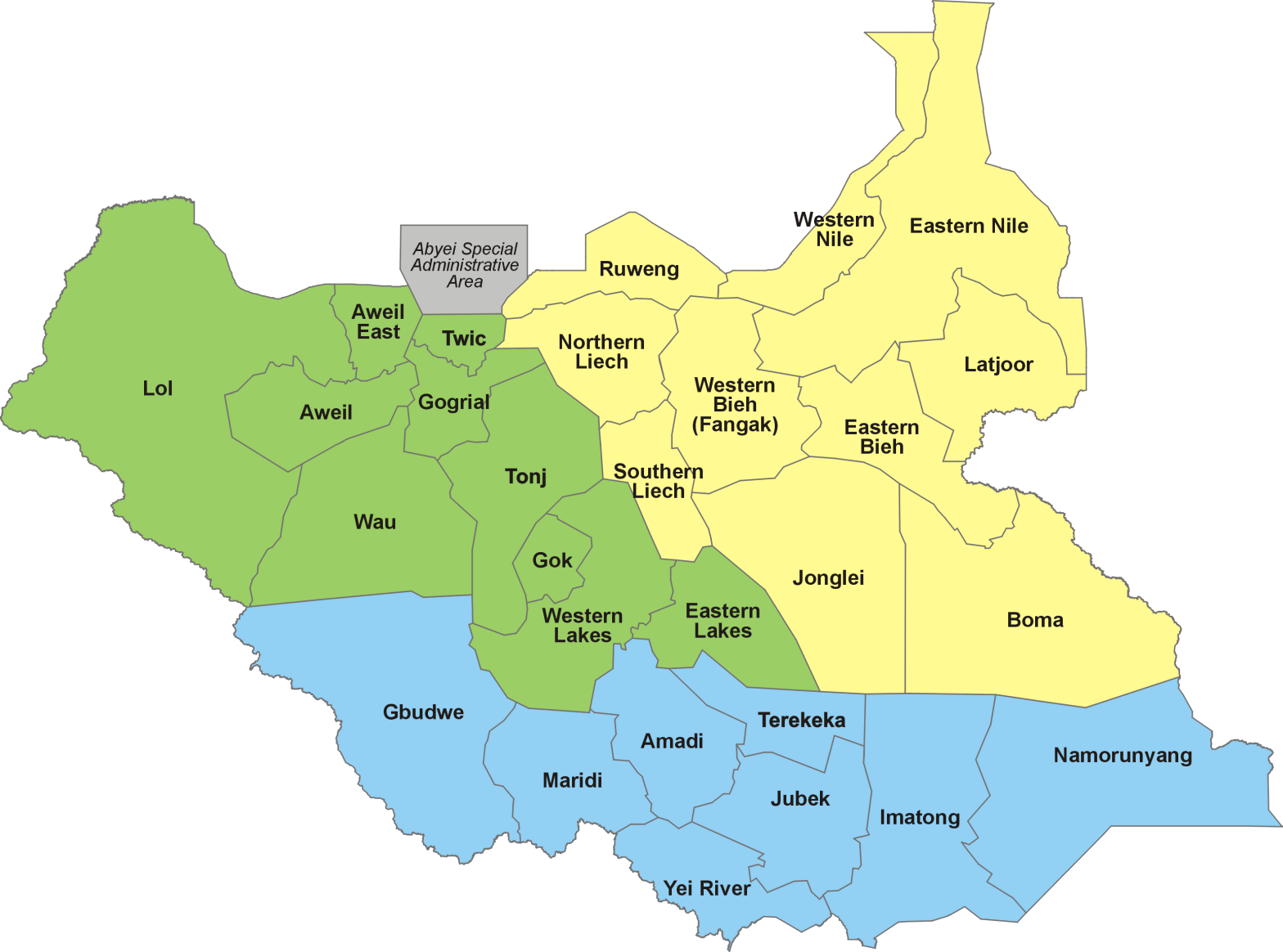

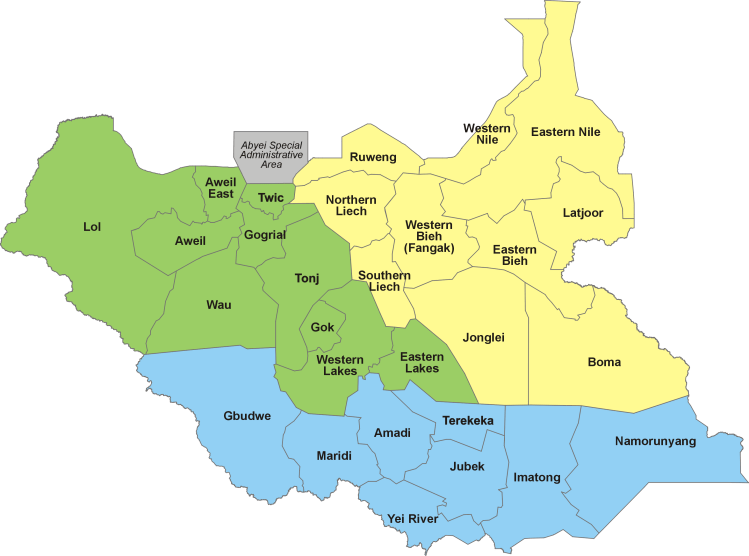

Landlocked by Sudan, Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Central African Republic, South Sudan achieved independence following a referendum that was 99% in favour of secession. Sudan – as it then was – was a British colony until 1956, overseen by a governor-general (appointed by the Egyptians under an 1899 agreement) and effectively governed as two territories, north and south. Upon gaining independence from the British, Sudan moved swiftly towards Sharia law and both an Arabisation and Islamisation of the country. This caused significant tensions with the south, which maintained the Christian identity it had developed under the British colonial system and rejected Muslim governance from Khartoum. After seceding, South Sudan adopted English as its official language and was split into 10 states, which were then re-orchestrated into the following 28 in 2015:

Source: Wiki Media Commons

Civil war erupted in the new state in 2013 between factions loyal to the president, Salva Kiir, and the former vice-president, Riek Machar. Kiir and Machar come from differing tribes – the Dinka and the Nuer respectively – and when tensions arose out of accusations made by the president that Machar had attempted a coup d’état, the conflict took on ethnic divisions, despite support for both men across ethnic lines at the time of independence. Around 300,000 people have been killed in the civil war, with particularly notable atrocities such as the Bentiu massacre in 2014, where the Nuer-led Sudan People’s Liberation Movement in Opposition Army killed over 400 non-Nuer civilians in churches, hospitals, and mosques. The civil war has seen South Sudan adopt the highest military budget as a percentage of GDP in the world, and has disrupted the development of infrastructure, government, public services, and industry. As of 2016, South Sudan places second on the Fragile States Index (formerly the Failed States Index), a report published annually by American think tank, Fund For Peace.

As the civil war continues, the tension between ethnic groups only increases, and the UN Special Advisor on the Prevention of Genocide, Adama Dieng, has warned of the “strong risk of violence escalating along ethnic lines, with the potential for genocide.” Those facing the strongest criticism are President Kiir and his government forces, accused of offensives against Nuer regions, where they “killed hundreds of civilians, raped woman and girls and stole thousands of heads of cattle.” The government’s actions in these regions have resulted in famine being declared; conflict and hunger have produced a mass of people on the move, both as internally displaced persons, and 1.2 million refugees outside the nation. Farmers do not want to return to their lands for fear of attack. This crisis has the potential to destroy South Sudan before it reaches its tenth year of independence and is a result of the underdevelopment and instability that is fuelled by the civil war and the Juba government. At present, the famine has already put 100,000 on the brink of immediate starvation, and threatens many more. Donations of food and aid money from the international community, both on the African continent and further abroad, will do little to help the situation if the root of the problem is not addressed.

Ethnicity and tribe matter in South Sudan, but the assumption that is often made in the West is that because there are strong community identities, there must be communal violence or ethnic conflict.is simply not the case. This was an avoidable crisis. The human rights of civilians, communities, and non-combatants in South Sudan are put at risk, and contravened, by the failure of both the Juba government, and the international community. Government forces, which systematically use ethnicity to target civilians and produce circumstances in which famine flourishes, should be held accountable. Thus far, the international community has failed to do so; no sanctions or punitive measures have been brought against either the government or opposition forces, the United Nations failed in 2016 to bring about an arms embargo over South Sudan, and the UN Security Council has sanctioned a grand total of two commanders.

Source: BBC News

Both the government in South Sudan, and the global community represented at the United Nations owe to the people of South Sudan a long-lasting solution to a rapidly worsening situation. Whilst aid money may offer a temporary sticking plaster, the fracture in South Sudan runs much deeper, and is much more serious than that. It is not enough for the international community only to be moved by images on television screens of starving babies: the human rights of the civilian population must be protected and situations like these must be prevented. Conflict resolution, peace building, and cooperative governance are not glamorous and don’t make for good news reports, but they are what will help save lives.