Photo by Jeanne Menjoulet on Flickr

The fetishisation of black women’s bodies is attributed to colonial times when black women were presented as hypersexualised, promiscuous wantons. As explained by Nefertari Bilal, when European colonisers travelled to Africa they met women who, to cope with the hotter climate, wore revealing clothes. Their exposed bodies contradicted the colonisers’ “Eurocentric standard of beauty” and perpetuated the belief that African women were sexually immoral Jezebels. The Jezebel stereotype was used to justify and rationalise the sexual assault of African slaves by their owners as it inferred that black women constantly desired sex and therefore, could not be rape victims. This was perpetuated even by abolitionists such as James Redpath who argued that black women appreciated the “criminal advances of Saxons.”

One woman who suffered in particular from the hyper-sexualisation of black women was Saartjie ‘Sara’ Baartman. Baartman was a Khoikhoi woman sold as a slave when Dutch colonisers invaded her land. Suffering from steatopygia (a genetic condition involving large accumulation of fat on the buttocks and thighs) Baartman was taken to Europe to be exhibited as a freak show attraction. Exhibited in Piccadilly Circus, and later across Paris, as the “wild or savage female” she was displayed in a cage and forced to perform supposedly ‘native’ dances half-naked while people poked her with a stick. Her “notable buttocks and spotty giraffe skin” were a source of fascination for the Europeans and became a symbol of her “uncontrollable sexuality.” She was even studied by naturalist George Cuvier who established her as a “link between animals and humans” and used her to confirm that Africans were an “oversexed” race.

Kim Kardashian’s highly controversial cover of Paper magazine back in 2014 caused outrage as her pose was considered a “not so subtle reincarnation” of Baartman. She was seen to be “endorsing the exploitation and fetishism of the black female body” while ignorantly reinforcing the Jezebel stereotype. This sexualisation of black women is also rampant in music videos. Black women are paraded around as sex symbols, draping themselves over expensive cars or male rappers. Nicki Minaj’s 2014 music video for Anaconda, is a perfect example of this. The video, which revolves around the theme of large bums, was lauded for “asserting her (Minaj’s) power, not as a sexual object but a sexual subject.” However, while some women may want to “reclaim and revise” the image of Jezebel to demonstrate emancipation from colonist interpretations, it is difficult to draw the line between the sex objects and the sexually liberated. Differentiating between women who “freely exploit their sexuality” and “repackaged Jezebels” is a difficult task.

Explained succinctly by Faatimah Solomon, the “fetishisation of black women’s bodies in their music videos translates into their hypersexualisation in the real-world.” In other words, depicting scantily-clad black women twerking for men’s pleasure creates dangerous stereotypes of ordinary black women. Dr Carolyn M. West, an expert on the psychology of women, argues that this Jezebel stereotype is inflicted upon black women even when they are not engaging in sexual behaviour. This perpetuates the idea that a black woman’s body is of more value than any other characteristic; her intelligence, education and professional successes are inconsequential as she is defined primarily by her sexuality.

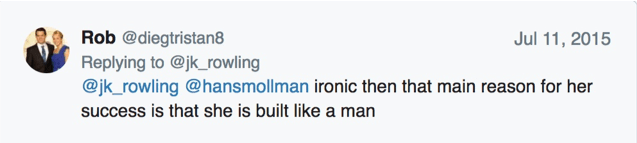

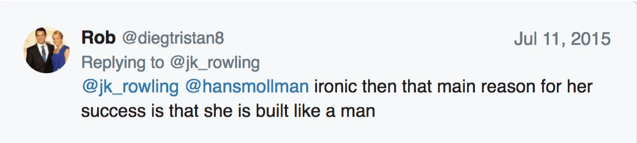

This is evident in the criticism faced by professional tennis player Serena Williams. Williams has been ranked the No.1 tennis player eight times in her fifteen-year career and, with 39 Grand Slam titles, holds the most titles of any active tennis player. However, her achievements are often overshadowed in the media by criticisms of her body. These range from critiques that she is “too strong” to the assumption that her successes are accredited to the fact that she is “built like a man”:

Source: Twitter

Dr David J Leonard, Professor in the Department of Critical Culture, Gender and Race Studies at Washington State University compiled a list of Tweets and YouTube comments following Williams Wimbledon victory in 2012. These were focused on her sexuality and her resemblance to gorillas, rather than her fifth Wimbledon title.

In another incident, President of the Russian Tennis Federation and member of the International Olympic Committee, Shamil Tarpischev referred to Venus and Serena Williams as the “Williams brothers” on a Russian TV show. Fellow tennis player Caroline Wozniack also stuffed her shorts and bra with padding in reference to Williams during an exhibition match against Maria Sharapova. Described by Yahoo News as “hilarious” and an “uncanny” resemblance to Williams, the incident was discarded as “light-hearted joshing” that should be brushed off by Williams. However, these instances reflect the prejudice faced by Williams not only by strangers on the Internet but by her peers. She is exoticised and sexualised while her physical appearance is the subject of mockery, much like Baartman. These incidents sadly depict how Williams’ achievements continue to remain secondary to her physical appearance.

This issue is compounded by the fact that a women’s sexuality and physical appearance is often the “only popular narrative available for black women.” There is a lack of “positive or realistic images to counter” these interpretations depriving young black women of much-needed role models in popular culture. However, there has been some diversification in the black characters depicted in mainstream media. Take for example the character of Jessica Pearson in legal drama Suits. A high-powered corporate lawyer and Harvard law graduate, Pearson overcame numerous challenges on her path to success and represents the difficulties faced by ambitious black women in environments predominately consisting of white men. These are the types of conversations we need to see more of in films, TV shows and music videos. There needs to be a greater focus on black women’s professional aspirations and academic achievements. This exploitation of their sexuality and the exoctisation of their bodies, which is prevalent in contemporary society, represents a serious and troubling lack of change over four centuries. Furthermore, it is every individual’s responsibility, regardless of gender or race, to be agents for this change.

#womensrights #racism #media #blackwomen #colonialism